An unexpected death in the Masai

I could not have imagined, when I was studying and writing down some historical information, that in this tribe, so beautiful, important and ancient, I would discover such a shocking custom, which really concerns me to this day, when I remember the stories of the Maasai. In my research, I was struck by the richness and culture of the Maasai, not found in other African tribes. I have, in the past, given a lot of information about their life and activities. However, when the question was posed, “What do the Maasai do with their dead?”, I got a thunderous answer! As recently as 50 years ago, maybe less, in the areas where the Maasai live, there was not even a question of burying the dead. – So what did the Maasai do with their dead? I asked a chief. – They threw the body of the dead into the forest with the wish that the hyenas and other wild animals would eat it, he replied. At this point I interrupted my conversation and thought I would look at things as they are today, to avoid the traumatic experience this information caused me. Fortunately, with the arrival of Christianity, this custom evolved.

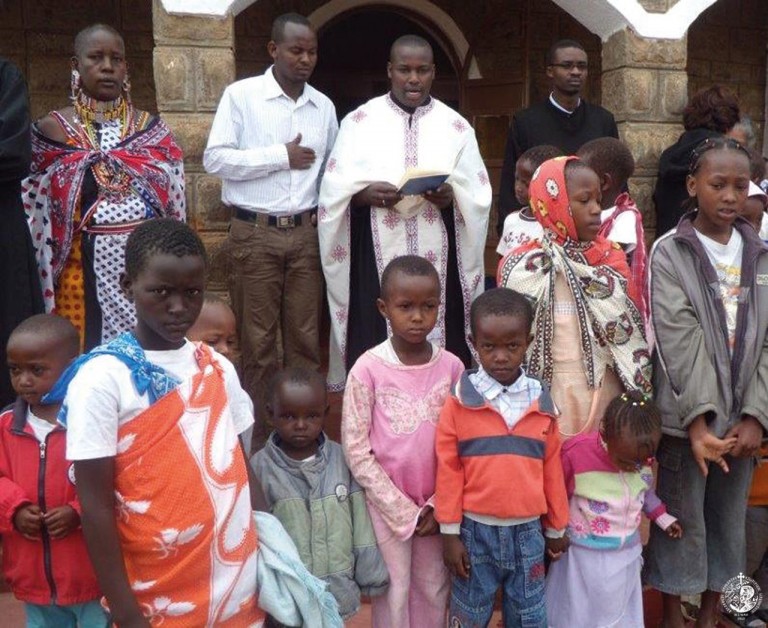

Thus, I have had the opportunity, in the course of more than 30 years since they came to know Orthodoxy, to see and experience the death of many people. It is a fact that funeral customs differ from one tribe to another. Most tribes give the impression that death is an event of great joy. Recently, I had the opportunity to attend a funeral of a young Maasai man whom I knew and who was interested in the next academic year to come to study at our Orthodox patriarchal seminary. George was a young man with rare spiritual gifts and I was already beginning to have thoughts that one day this boy would become a good priest and help the Maasai communities. For unknown reasons, while I spoke to him the day before his death, he did not disclose to me that something was wrong with his health and while I was on a tour in western Kenya, his younger brother called me and announced that, under unknown circumstances, he had surrendered his spirit. In order to be able to attend the funeral, I interrupted my tour and immediately arrived at the place where it was to take place. A large crowd, hundreds of Masai in their traditional costumes, surrounded the place. In particular, young people of the same age as George. After we had the church funeral, speeches were made by both his relatives and the village authorities. The whole atmosphere was not at all joyful, as is the case in other tribes, where they dance and sing non-stop for hours on end. The Maasai were quite different. I did not notice any cultural ceremony with the usual traditional songs and dances. On the contrary, the people were silent and watched with devotion, especially the bishop’s speech.

It was not the first time I had been given this opportunity to speak at a Masai funeral. And on previous occasions the funeral was again for young people, so I took the opportunity to emphasise the great sensitivity that people usually have in these situations, knowing that the death of a young person certainly causes deep sadness, not only to their peers and friends, but more so to their family members. It was yet another opportunity, while briefly recalling, to remind the elders of their ancient custom of throwing the dead person into the forest without a second thought, so that his body could become food for the wild animals. It is a fact, through studies made, that the Maasai from ancient times have despised death. This was the reason why this custom prevailed. That is, in order not to think too much, to torture their minds, to grieve and perhaps even to spend themselves, they found this solution. In fact, they were materialistic and had no deep spiritual experience. Their spirituality could only be described as rich and rare through their own reality, i.e. they gave the image of the “good savage” as described by the 18th century writers Rousseau and Voltaire. So, on that day, I wanted to convey the message of the resurrection of the dead, because I knew that people of all ages and diverse beliefs – baptized, unbaptized, educated, uneducated – were attending the funeral. Perhaps, on that day, people realized, for the first time, how much importance Orthodoxy attaches to the person of man, recognizing him as an image of God. Certainly, for their own standards, this represented a new hope, opening new horizons for their spiritual formation and advancement. Let us not forget, then, that we are talking about people who a few years ago had wild dispositions towards their fellow men, and therefore it meant nothing to them that any situation that led them to death.

What impressed me was the orderliness, the seriousness and the silence, no noise, no shouting, no dancing, no singing. Quietly they lowered the coffin of the young dead man into the grave, covered it with that hard soil of the Masai earth, and then, in silence, they departed. After the funeral, we sat down under a tree, where the young people surrounded me and began to ask me questions about the afterlife, about the resurrection of the dead, as I described them in my talk. They showed such interest and understanding that I realized that these people were strongly lacking in catechetical teaching and the depth of Orthodox spirituality in relation to death. I thought it was the most appropriate time, at least for the young people, to give this message of hope, of eternity and expectation, of the resurrection of the dead at the second coming of Christ. May these efforts that we are making, not only with the Maasai but also with the other tribes, be able to offer the true meaning of Orthodoxy to the souls of these suffering people, who long to know and taste the flavours and ethos of our Orthodox faith as the one, single, holy, catholic and apostolic Church.

† The Kenyan Macarius