St. Zotic: Orphanage and Mission

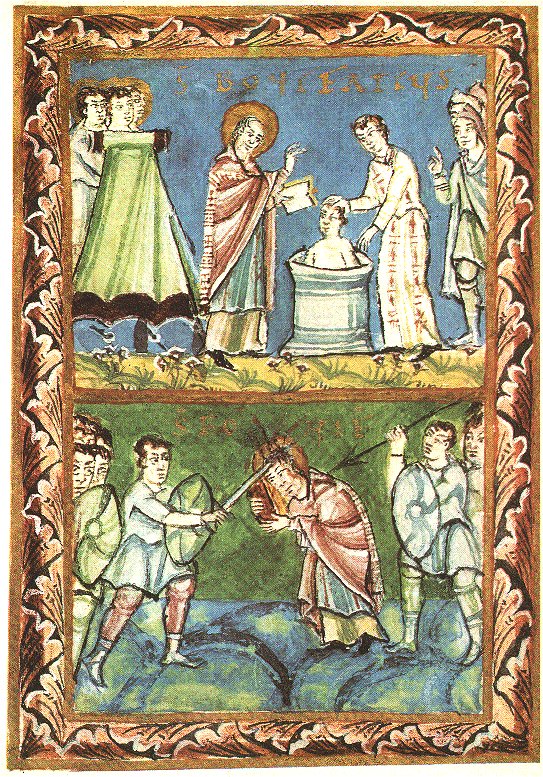

Zoticos lived during the reign of Constantine the Great and then of his son Constantine. He was a native of Rome, of noble birth, and was educated both in letters and in Divine Wisdom. When Constantine decided to move the capital of the empire to New Rome, Constantinople, he asked that his Magisterian, Zoticus, should follow him. And so he did. It was at this time that leprosy, which was believed to be contagious, “hit” the empire. As St. Nicodemus reports, the emperor enacted a harsh law, according to which anyone who suffered from the above disease would be thrown into the sea to avoid spreading it. The sensitive Zoticus could not stand it and took action. He appealed to the king asking for gold and promised him that with it he would buy pearls and gems to offer to him and the empire. Constantine relented and granted Zoticus as much gold as he needed. Immediately, the Saint came to an understanding with the soldiers who were assigned to kill the lepers. Bribing them, he bought the sick, transported them to an area outside Byzantium, made tents for them to live in, and tried in every way possible to ease their pain. Constantine the Great died and Constantius, who did not like Zotius, who belonged to the Orthodox, and who himself supported the heretics, took over the administration of the empire. He also believed, on the one hand, that the Saint would be responsible for any transmission of the leprosy epidemic to the empire and, on the other hand, he considered him the main culprit of the economic crisis it was facing, since Zoticus was spending large sums of money not only to buy the sick but also to treat them. So much was Constantius afraid that he even handed over his daughter to be killed – an act which the Saint prevented in the usual way – because she had contracted the disease in question. It happened, therefore, that during the Saint’s charitable work, as we have hinted above, a famine fell upon the empire. Immediately, Zoticus was presented by his diabolical enemies to the emperor as the chief cause of the misery that befell the empire, and he was made the scapegoat. Then the king, influenced by his close entourage and having a strong dislike for the Saint, ordered Zoticus to be arrested. He, however, appeared before Constantine before his order could be carried out. In a stern yet ironical tone, the emperor asked him if he had brought with him the gems that both his father and he had sponsored him to find. The answer was in the affirmative; as long as he followed him, he would see them. So he led the emperor to the place where he sheltered and cared for lepers. Then the stagnant waters of Constantine’s hardy heart were troubled, not, however, by compassion and love – even when he met his daughter alive long afterwards – but by anger and hatred, both for the lepers and for their patron.

He was sorry that he did not see precious stones and pearls, he was disgusted that he saw sick people, he was offended that the Saint deceived him. He did not know that for God’s people the ministry of a fellow man – whether he is sick or an orphan or any orphan – receives a greater reward from the Lord than pearls and priceless stones. He did not know that for the man of God the other man is not his enemy or his worst nightmare, but is the most precious means of his salvation. He did not know that for Christians there is a “discipline to see the things of men” (Acts 5:29) . The Emperor’s order was immediate and imperative; death to the Saint, the merciful one, to the one who so underestimated death, to the one who by his love defeated the death of his countrymen. And he was led instead of them to death – as a true child of the sacrificed Son of God – which was but the pathway leading to life, to eternity. A martyr’s death, cruel and gruesome; they tied him to two horses and pushed them in opposite directions, so that he was dismembered. It was a heroic death, an act of life with an aura of heaven.

Orphans and mission

Studying the life of Saint Zotikos the Orphanotrophos, a legitimate question arose in my mind regarding his nickname. The saint was a protector of lepers; why was he called “Orphan Farmer”[1]? A more penetrating look into the inner world of these sick people reveals, I think, that – cut off from their loved ones and society, considered disgusting, infected and dangerous, deprived of affection and care, constantly facing the threat of death – they felt more orphaned than orphaned children. Still, leprosy may indeed have afflicted young children who were separated from their parents and family in general, such as the emperor’s daughter. Those suffering from the disease, which was so prevalent at the time, were either condemned to death – as we have seen – or, at best, were in exile far from their homeland, their loved ones and their very lives.

But what does the life of the Saint have to do with the Mission?

Each missionary suffers some of the consequences of the above disease and at the same time follows in the footsteps of the holy Zotikos, since from the beginning of the effort to realize his choice, he abandons his life, his homeland, his relatives – parents, relatives and friends -, his habits, and goes into self-exile in order to spread and apply the Gospel in “foreign lands”. Why? To feed the hungry, to speed up the imprisoned, and to “oversee those who are in darkness and the shadow of death” (Luke 1:79). Even if the above view contains nuggets of truth, we would be remiss if we did not expose that a crucial task of the Orthodox internal and external missionary work is the defense and care of orphans: Orphan children by creating orphanages; “orphans” of the sick by building hospitals; “orphans” of the neglected by making soup kitchens; “orphans” as far as the knowledge of the Truth of Christ is concerned by building churches and establishing Sunday schools; and “orphans” in education by building schools of all levels.

Of course, by using the term “orphanhood” (which normally means children without parents) we do not diminish or -better- underestimate its importance, we simply emphasize the loneliness and alienation from the whole world, which all the above-mentioned situations cause. On this subject, St. Chrysostom also aptly emphasizes:

“Indeed, there is nothing more painful than orphanhood, when age is not enough for anything for orphans, and there are no true protectors, and crowds of people appear ready to attack and stud them, and the orphans are exposed like lambs among wolves, who on every side devour them and tear them to pieces. No one can represent in words the magnitude of this calamity. Hence Paul, after carefully searching for a word indicative of the desolation and painful calamity, to represent that he was suffering, separated from his loved ones, used the word “vanished away” (H.P.E. vol. 37, pp. 423-425).

The memory of Saint Zotikos is celebrated on 31 December.

Apolyticon.

Sound c. Divine Faith.

O great living and joyful Martyr, perceiver and protector, the lepers, the orphans and the mourners, and those who are afflicted with infectious diseases. As thou hast poured forth a fountain of holiness, from thy relics, I have cured all sickness, I have cured leprosy, and I have protected thee, all the honorable.

Eteron Apolytikon.

Sound pl. a. The synaesthetic speech.

O living King, thou hast taken the gold of the King, Constantine and his lepers, healing the merciful God in them, having forsaken life, and not fearing, O Father, the passing on of a terrible disease: for thou hast been restored to angels, having been bound for us for ever.

[1] Orphanotrophos was a Byzantine high-ranking political, judicial and religious office and referred to the person in charge of one or more orphanages. Both he and the orphanage were not under the control and care of the Church, but were under state support in Constantinople.